Panic Disorder & Substance Abuse in a Dual Diagnosis

Understanding Panic Disorder through the DSM-5 framework highlights the critical nature of accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment. Despite the effectiveness of benzodiazepines for short-term relief, their potential for dependency underscores the necessity for cautious use, especially considering the risks of exacerbating anxiety symptoms.

Panic Disorder: The DSM-5 Approach

Panic Disorder, as detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), is a mental health condition characterized by recurrent and unexpected panic attacks.

These attacks are sudden surges of intense fear or discomfort that peak within minutes, accompanied by physical and cognitive symptoms that can significantly impact an individual’s daily life. The DSM-5 outlines specific criteria and features for the diagnosis of Panic Disorder, emphasizing its distinction from other anxiety disorders.

Diagnostic Criteria for Panic Disorder

Recurrent Panic Attacks

The core feature of Panic Disorder is the occurrence of recurrent, unexpected panic attacks. A panic attack is an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that reaches a peak within minutes, during which time four (or more) of the following symptoms occur:

- Palpitations, pounding heart, or accelerated heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Sensations of shortness of breath or smothering

- Feelings of choking

- Chest pain or discomfort

- Nausea or abdominal distress

- Feeling dizzy, unsteady, light-headed, or faint

- Chills or heat sensations

- Paresthesias (numbness or tingling sensations)

- Derealization (feelings of unreality) or depersonalization (being detached from oneself)

- Fear of losing control or “going crazy”

- Fear of dying

At Least One of the Attacks Has Been Followed by 1 Month (or More) of One or Both of the Following:

- Persistent concern or worry about additional panic attacks or their consequences (e.g., losing control, having a heart attack, “going crazy”).

- A significant maladaptive change in behavior related to the attacks (e.g., behaviors designed to avoid having panic attacks, such as avoidance of exercise or unfamiliar situations).

The Disturbance is Not Attributable to the Physiological Effects of a Substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or another medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism).

Another Mental Disorder does Not Better explain the Disturbance:

For example, panic attacks do not occur only in response to feared social situations, as in Social Anxiety Disorder, or response to circumscribed phobic objects or situations, as in Specific Phobia.

Features and Symptoms

Individuals with Panic Disorder may experience intense anxiety and fear about the possibility of having another panic attack, which can lead to the avoidance of situations where attacks have occurred or where escape might be intricate. This anticipatory anxiety and behavioral avoidance can significantly impair occupational and social functioning and in severe cases, can lead to agoraphobia.

Differentiation from Other Disorders

Panic Disorder must be differentiated from other anxiety disorders and conditions that may present with panic attacks, ensuring that the diagnosis is specific to the pattern of recurrent, unexpected attacks and the subsequent worry or behavior changes.

Treatment for Panic Disorder

Treatment for Panic Disorder typically involves a combination of psychotherapy (particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy, CBT) and medication (such as SSRIs or benzodiazepines in the short term). CBT is effective in teaching coping strategies to manage and reduce the frequency of panic attacks and the fear of future attacks.

Understanding Panic Disorder through the DSM-5 framework is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment, enabling individuals to manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

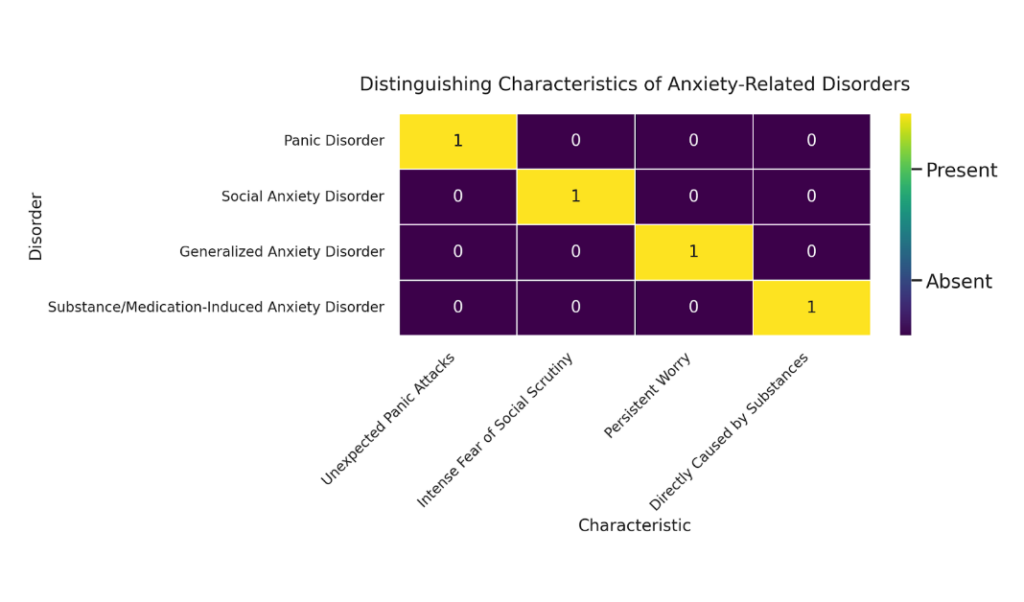

Anxiety Defined: A Comparative View of Disorders

The chart visually distinguishes Panic Disorder from Social Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), and Substance/Medication-Induced Anxiety Disorder based on specific characteristics.

Each disorder is uniquely identified by its defining features, such as unexpected panic attacks for Panic Disorder, intense fear of social scrutiny for Social Anxiety Disorder, persistent worry for GAD, and direct causation by substances for Substance/Medication-Induced Anxiety Disorder. This differentiation aids in understanding the distinct nature and diagnostic criteria of these anxiety-related disorders.

Fact Versus Fiction: The Truth About Panic Disorder

There are three common misconceptions about panic disorder. These beliefs can be obstacles in the path to seeking effective treatment.

Misconception #1: Panic Disorder is just an overreaction to stress and can be controlled with willpower.

Fact: Panic Disorder is a recognized mental health condition characterized by recurrent, unexpected panic attacks. These are not simply stress responses but involve complex physiological and psychological processes that require professional treatment.

Misconception #2: Panic attacks cause fainting, heart attacks, or are life-threatening

Fact: While panic attacks are intense and can feel catastrophic, they are not physically dangerous. They do not cause fainting (which is a response to a drop in blood pressure, whereas panic attacks increase blood pressure) or heart attacks. Understanding this can reduce fear and the perceived threat level of attacks.

Misconception #3: Panic Disorder will go away if you avoid situations that are stressful.

Fact: Avoidance may temporarily reduce the likelihood of an attack, but it reinforces the disorder in the long term. Effective treatments such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) often involve gradually facing and accepting the physical sensations of panic in a safe and controlled manner to reduce avoidance behaviors and the power of panic attacks over time.

Benzodiazepines in Panic Disorder: The Pitfalls of Dependency

Commonly prescribed medications like benzodiazepines are considered to have considerable risks when used in the treatment of Panic Disorder due to their high potential for dependency and addiction.

Here are some common benzodiazepines prescribed for Panic Disorder, along with their generic and brand names and the associated dangers:

- Alprazolam (Xanax): Risk of dependency is high; withdrawal can include severe anxiety, insomnia, and seizures. May cause cognitive impairment and has a high potential for abuse.

- Clonazepam (Klonopin): Long half-life can lead to accumulation in the body, increasing the risk of sedation, cognitive dysfunction, and dependency.

- Lorazepam (Ativan): Can cause paradoxical reactions such as increased anxiety, as well as withdrawal symptoms even with short-term use. Risk of tolerance and dependency is significant.

- Diazepam (Valium): The sedative effects can impair motor skills and cognitive functions; the potential for dependency and withdrawal is considerable, especially with long-term use.

- Oxazepam (Serax): Lower abuse potential than other benzodiazepines but still can lead to dependency and withdrawal, especially with prolonged use.

Each benzodiazepine carries risks, particularly with long-term use. The dangers often include dependency, withdrawal symptoms, cognitive impairment, and the potential for abuse.

Consequences and Symptoms of Dependency

- Tolerance: Over time, the body may require higher doses of benzodiazepines to achieve the same therapeutic effect, leading to increased consumption.

- Dependence: The body may become reliant on the medication to function normally, and cessation can lead to withdrawal symptoms.

- Withdrawal: Symptoms can include rebound anxiety, insomnia, restlessness, agitation, tremors, and, in severe cases, seizures.

- Cognitive Impairment: Long-term use can lead to memory, attention, and coordination issues.

- Exacerbation of Symptoms: Dependency can paradoxically worsen anxiety over time, leading to a cycle of increased use and heightened anxiety symptoms.

Other Commonly Abused Substances in Relation to Panic Disorder

- Alcohol: Often used to self-medicate due to its initial calming effect, but it can worsen panic symptoms as it wears off.

- Cannabis: Some individuals use cannabis for its anxiolytic properties, but it can also worsen panic attacks in certain strains or doses.

- Stimulants: While not typically used to self-medicate for Panic Disorder, substances like caffeine can exacerbate panic attacks.

Complications with Panic Disorder

- Dual Diagnosis: The co-occurrence of Panic Disorder and substance abuse creates a dual diagnosis, complicating treatment and recovery.

- Treatment Interference: Substance abuse can interfere with the effectiveness of treatment for Panic Disorder, masking symptoms and making it harder to assess progress.

- Risk of Relapse: Those recovering from Panic Disorder who abuse substances may be at higher risk of relapse into panic symptoms.

The complexities introduced by the abuse of benzodiazepines and other substances necessitate a careful, integrated approach to the treatment of Panic Disorder. Alternative treatments, such as SSRIs, SNRIs, and psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), are recommended due to their lower risk of dependency and their effectiveness in addressing both the physiological and psychological aspects of the disorder.

From Theory to Therapy: Clinician-Authored Books on Panic Disorder

Below are three books authored by licensed clinicians who are recognized experts in the field of panic disorder. These books are written by professionals with authoritative knowledge of panic disorder, providing readers with reliable information and evidence-based strategies for managing this anxiety disorder.

"The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook"

by Edmund J. Bourne, PhD

Dr. Bourne, with his extensive clinical experience in the treatment of anxiety disorders, provides a comprehensive resource for coping with and overcoming panic attacks and phobias.

"When Panic Attacks"

by David D. Burns, MD

As a psychiatrist and renowned expert in cognitive-behavioral therapy, Dr. Burns offers practical techniques and exercises to help individuals change negative thought patterns and alleviate panic symptoms.

"Panic Disorder: The Medical Point of View"

by William D. Kernodle, MD

Dr. Kernodle, with his medical expertise, discusses panic disorder from a physiological perspective, offering insights into medical treatments and the biological underpinnings of panic attacks.

Reflections on Panic Disorder

Final Words for Families Considering Long-Term Treatment

Understanding Panic Disorder through the DSM-5 framework highlights the critical nature of accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment. Despite the effectiveness of benzodiazepines for short-term relief, their potential for dependency underscores the necessity for cautious use, especially considering the risks of exacerbating anxiety symptoms.

Emphasizing alternative treatments, like cognitive-behavioral therapy and SSRIs, offers a safer, more sustainable approach to managing Panic Disorder, ultimately improving individuals’ quality of life and mitigating the risk of substance abuse. This comprehensive understanding facilitates a balanced treatment plan, integrating both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic strategies to address the multifaceted challenges of Panic Disorder.